Fall 2012 Research

Pre-Columbian

My art history piece for the semester is primarily based on a piece called the Aztec Calendar Stone or Sun Stone, carved in the fifteenth century. Very little is known for sure about the meaning or purpose of this piece. Theories range from a calendar, because of the presence of the four directions and images for the twenty days and months of the year to a basin for ritual sacrifice.

I used this image as a launching point for decoration of a 25-pound platter that was thrown on the wheel. With this piece as a launch point I then looked at other art images from Mesoamerican art history to help build a body of images to decorate my personal statement about the end of one time and the beginning of another.

I began with the Mayan Vision Serpent. This image appears in many works of art from the Mayan culture and is among the most important figures in the cosmology of the culture. The serpent is associated with bloodletting rituals that were thought to give the seeker visions. The serpent is a gateway to the spirit realm. The ancestor or god being sought emerges from the mouth of the serpent to communicate with the seeker. I modified this image to both fit my style of drawing a bit but to also fit the largest band of the platter. Three serpents ring the platter, moving in a clockwise direction, countering the direction of the wind (representing change) in the small ring outside the center of the platter.

The next image used to create my cosmology in the plate is the World Tree. The tree I used is from a painting from the Popol Vuh, a book of the Mayan culture that tells creation myths and other specifics of the belief systems of the Maya. This image tells the story of the creation of the fourth type of humans at the beginning of the current age. It depicts the Twin Heroes killing Seven Macaw, the ruler of the previous age. Again I drew the tree to fit the plate and to reflect aspects of it I felt compelling. The world tree itself is at the center of the Mayan Cosmology, holding up the vision serpent. It represents the four cardinal directions and connects the four worlds.

The last image chosen specically for the plate is a part of the Aztec Sun Stone. At the bottom of the stone are two figures. The hold their origional meaning no my tribute to the origional. They are the sun god Tonatiuh and night god Xiutecutli, facing eachother. While not wanting literlally to evoke those ancient gods I did want to represent the pairs of opposites that define a human understanding of the world, the relationship of the opposites being the foundation of how we make sense of change. I also wanted to directly reference the origional piece in a way to make its influence more recognizble.

I then populated the rest of the plate with images from my own cosmology. Simple symblos that apear again and again in my work. Flaming hearts and skulls alternate with an image of the wind, representing change and constancy. A large butterfly represents emergence from a time of darkness. The crow means family and courage. The fox represents myself. Also present art large triangle elements also taken from the origional piece that point to the cardinal directions.

This was a wonderful project and I really loved getting to know the art of Mesoamerica more thouroughly. While ancient art in general has been a strong influence I my work always I had never spent much time with the cultures of early Mexico and Central America. I found wonderful parallells with so much of my earlier studies and feel confident this research will remain a strong influence on future work

Katy Jones

Ancient Mayan Temples

The Mayans were credited with being a very advanced civilization, though they lacked modern technologies. They were able to achieve things that were thought incapable, such as mathematics, language, the development of calendars and the building of very large structures. Most impressive of the massive structures that they built were their temples. Though there is not much information on the Mayan temples, it was believed that they were built in order to honor their gods. There are temples located in Altun Ha, Caracol, Lamanai, Tikal, Tulum, Chichen Itza, and Palenque, which are cities located around central and South America. (www.globalsherpa.org) These temples were significant in Mayan culture because the Mayans believed that they had to please their gods in order to keep living in prosperity. The way that they decided to do this was through ritual human sacrifice. This was a very important part of Mayan life, “The religious acts were performed on certain fixed dates, and were considered necessary in “order to hold the world in its orbit and prevent it from falling into an abyss of nothingness. Sacrificial rites and rites of purification in honor of the gods of the rain and the sun were considered essential to the prosperity of the agriculture on which the Mayas depended”” (Esther) For these ceremonies the Mayans needed a sacred place to perform the sacrifices, which made the temples the ideal place for such rituals. Not only was this an important part of life, but it was an event that came to became an honor. The Mayans chose to sacrifice those that they thought would please the gods the most such as those who were skilled athletes at the ball game.

I found the Mayan temple to be very intriguing because they showed such skill and craftsmanship for a culture that didn’t even have access to metal tools, due to the fact that there wasn’t yet the technology to make such tools. It also interests me that in the Mayan culture, that they thought the world would end unless they sacrificed humans in order to please the gods. This all happened due to the fact that at the time, the best explanations that they had for natural phenomena, was that it had to due with the gods. At the time that they didn’t have scientific explanation in order to describe what was happening. Without this explanation the best that they could do was to please their gods and hope that if they kept sacrificing enough people that their world wouldn’t just drop into oblivion. It is also amazing that for a culture with such primitive tools were able to create such large, impressive structures. Though it’s hard to believe that they were able to achieve such greatness is hard for people in the modern era, however, due to the fact that some of these almost megalithic structures are still standing, there is no denying that the Mayan culture was very advanced for their time.

Katy Jones

Azuzul Twin

The Azuzul twins were found in the El Azuzul archaeology site, which is located in Veracruz, Mexico. (Burnham) Part of well know Tenochitilán city, though it is a few miles away from the main city, El Azuzul presents archaeologists with a well preserved look into the past at Olmec art. (Burnham) This is the site at which the Azuzul twins, as they have become popular called, were discovered. (Burnham) These sculptures are considered to be very important to understanding ancient Olmec art, “The first pair of statues have been hailed as the masterpieces of Olmec architecture, they are expressive and refined, with a mastery of technical aspects evident in the form of conception of the sculptures.” (Burnham) What is being stated is that because these figures were so well preserved, an understanding of the human form by the Olmecs could be observed by modern archaeologists. These figures, which now reside in the Museo de Antropologia in Xalapa, Mexico, were found directly behind each other in an Eastern orientation. (Burnham) Archaeologist speculate, that these twins, for lack of a better term, could have possibly been Mayan heroes or Priests. (Burnham) Both twins appear to be grasping some sort of ceremonial staff, which is believed that they used for growing a world tree. (Burnham) These figures were also located facing two other figure that had cat-like appearances. (Burnham) These feline figures were more than likely Jaguars, since jaguars were highly revered animals in the Olmec cultures. This figure depicts a man, sitting on his knees, leaned over what appears to be a staff of some sort. He appears to be in traditional clothing, judging by other figures that have been found. However, this figure does seem to have much more ornate clothing than what seems to be the traditional type of dress, seeing as how his chest is covered. The man also wears a headdress which is reminiscent of those worn in ancient Egypt. This is not thought to be such a far stretch due to the fact that at the same time that this figure was thought to be produced, 2,000-1,500 B.C.E, is the same time at which the Egyptians were in their Old kingdom period of the Egyptian era. This similarity indicates that Egyptians could have possibly been the area and had some type of influence on the Olmecs. However, this figure does differ greatly from how the Egyptians constructed their figures, due to the fact that for many years, the Egyptians relied on big, supportive, blocks to hold up their three dimensional sculptures. These Olmec sculptures of the twins show an advanced knowledge of the human form as well as advanced knowledge in the material that they were building with. Though the form is rigid, there is still the indication of movement and expression throughout the body of the figure. There is also quite a bit of attention to detail to the face, clothing, and headdress, which indicates that the Olmecs were much smarter that we like to give them credit for in modern day. I personally don’t connect with the Olmec art. I find the megalithic figures to usually be crude and un-detailed. However, I found the Azuzul twins to be quite the opposite of my misconception of Olmec art. I found this piece interesting, because I could see expression in the form, even though it was stiff and rigid, it could still be seen that the figure was trying to convey a common happening in the Olmec culture. I was also very impressed by the mastery of the material. In our society we usually like to think we’re much more advanced than our ancient ancestors, however, the intricacy of this figure seems to prove that common stereotype wrong, at least in regards to art. Works Cited:

Burnham , Andy. “The Megalithic Portal.” El Azuzul-Pyramid. N.p., n.d. Web. 19 Oct 2012. <http://www.megalithic.co.uk/article.php?sid=30046>.

Sharon McCoy

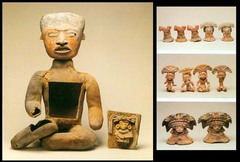

The Bat God From Oaxaca The ceramic piece that chose to report on is the Zapotec Bat God Funerary Urn because of its resemblance to the Chinese Sancai or Zhenmushou “tomb guardian” or “earth spirit”. Other cultures’ burial rituals and practices are interesting to me. Death practices have much to say about how a culture lives and what is important to them. The objects that they place at burial sites and tombs give much insight into the civilization. The fanciful rendition of a bat or jaguar functioned as a funerary urn from the pre-Columbian era from Oaxaca in the southern portion of Mexico. The Zapotec people occupied the Oaxaca Valley beginning in the late sixth century AD and they are still living there today. The vessel is only 9.5”. It was made during the third phase of the Monte Alban Complex History dating between AD 300-650. The piece belongs to the American Museum of Natural History, in Manhattan, New York. Most of the urns that were created by the Zapotec people have burial significance and have been found in and around tomb sites. They sometimes created niches outside the tomb or in an antechamber room before the main tomb. Some of these effigies have been found in compartments under the floor in tombs or in special boxes outside the tomb structure. The figures vary in size from 2.5” to 24”. Often they are created in a series. Oaxaca ceramics are generally made of a ”fine gray paste” and several have layers of red pigment that is believed to be cinnabar. Some, however few, are polychromed or finished in white. Usually the vessels are found with nothing in them; if there had been contents, it had been removed with time. There was a vessel found with bones of a bird and one found with “green stone figures” that were possibly meant as offerings. The urns are seldom found by themselves, but they are found with other objects made from clay or stone. Many of the vessels are found worn or broken giving indication that they were used more than once. Even with the many studies that have been done on burial vessels in the twentieth century, there is not much agreement on the symbolism behind them. This leaves little to extrapolate knowledge of their religion and rituals; only speculation. One such speculation was that the urns were from a complex collective of gods, but researchers are not even sure that the Zapotec people had deities and revealed their kings thinking them to have afterlives. Others believe that the effigies bear a resemblance to the costuming of characters on their calendar. However, those characters are somewhat the same as other Meso-American cultures, so they could be a pantheon of gods. Some studies show that the images are deities of the cosmos, a type of heaven and hell. Possibly still, they are kings made up to be gods that represent the Meso-American calendar. There is no evidence that the Zapotec people performed cremation so the function of these vessels probably was not for ash remains. The Zapotecs had their own logo-syllabic written system for their calendars that used glyphs. This bat god urn has glyph markings down the side of his mouth that is where blood would stream from its mouth. With large monkey like ears, a face like a lion, four legs with claw toes and a tongue dangling out between many teeth from a dimpled toothy grin, it is hard to determine what this hybrid really is. It wears a necklace that has a simple hieroglyphic symbol with what looks like either three bells or figs. I find the stylization of this figure as wonderfully whimsical instead of frightening. This interesting vessel is a highly mysterious figure because of the uncertainty of what it was used for and its symbolism represents.

Dani Bullard

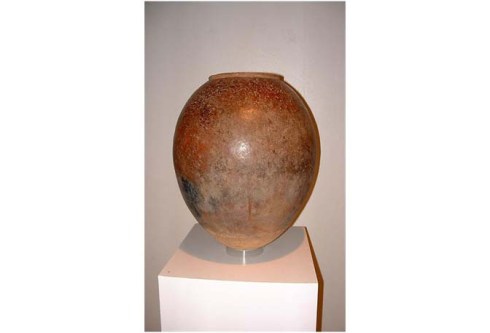

Pre-Colombian Tripod Vases

These vases were created between 400-700 BCE by races like the Inca, the Myan’s and the Olmec. These pieces were probably created out of need for function and balance on an un-even surface, for a flat bottomed vase would not rest well on an un-even stone or dirt surface. These ancient races lived on packed soil or stone floored housing, so they often created functional vessels that had rounded or tripod based foot system, that allowed them to be positioned in a divot on the floor, or balance themselves, in this case, on multiple points of contact. Ancient civilizations such as the ones that created these pots were very ritualistic and based their lives on the worship of gods or deities, like Quetzalcoatl, the feathered serpent, and often had a musical or vocal aspect in their every day lives. These pots may also have doubled as musical components for these rituals. The legs are hollow and may have been rattles at one time, but the internal pieces are no longer intact. These pieces were hand built using coil building techniques because they lacked the technology for wheel spun creation. They were created using an earthen ware, or red iron rich clay body and fired using a wood fired method.

My art history piece this semester is my first music box. It is not meant to be placed on a packed dirt floor, and was not created with any consideration of its ability to sit well on un-even surfaces. It is strange that a common functional element from their time is simply used aesthetically today. I used the tri-pod foot system to raise the piece off its sitting surface, and to create a dainty, precious, hovering effect. This piece is similar in that it has tripod feet, but also that it has a musical aspect as well. It has a small opening in the bottom to fit the turn key of a music box, The pre-Columbian artist used ceramics for its musical qualities, and I myself was surprised at the resonance the ceramic body had when the music played from within. The music box I chose plays a melody with special meaning to me, and relates to their ritualistic use of the instruments of worship in their lives. Though I used completely different methods, and desire for creation, the effect is surprisingly similar.

Kayla Hern

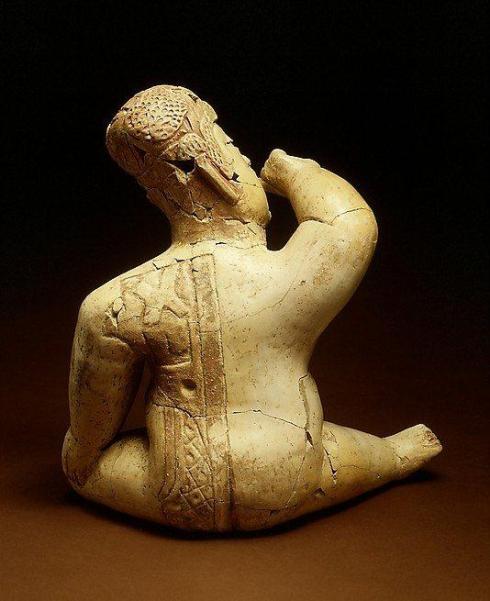

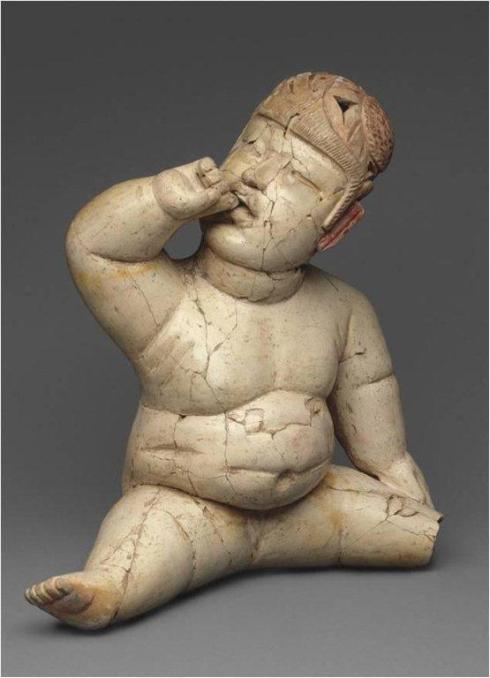

This semester through all of the art history from African and Pre- Colombian art I found that the child like figures related to me the most. I was really drawn into this little child figure that was created in the 12-9th century BCE and crafted in Mesoamerica, which is in Pre-Columbian Mexico, by the Olmec population. They created many different child figures that were made of clay and used cinnabar and red ochre on them as well. As long ago as these figures were created, they were well crafted for this time period because they did not have as many advanced tools as we have in today’s society. Although the figures are really simplistic in features they still are one of the most popular art forms that the Olmec created during this time. These figures are thought of as symbolizing deities or emblems of royal descent but no one is really certain what they really symbolized for Pre- Colombian Art. This figure looks so plump and mis-proportioned for a realistic baby. This figure is made of white clay and is hollowed and is you can see over time that the leg has broke off of the child. This figure is really interesting because it has a helmet on and it makes you wonder why would a baby have one on. Or it is said that it could be a hairpiece. As you look at the second picture it is showing the back of the figure, which shows great carving skills and creates a very interesting texture on the figures back.

These little Olmec figures relate to some of the work I did this semester because I created one of my first figure torso. I related it to this figure because I have a lot of textured areas on the figure and I also had to work on creating realistic features in the face, hair, and hands, which was very difficult. As this child figure might have represented a royal decent, my figure that I created this semester was to resemble my aunt. Therefore the Olmec figures inspired me to create a figure that on inspires but touches people’s lives.

Dayna Ball

The Maya, Zapotec, Mixtec, and Aztec religions all considered human life to be indicative of a larger life cycle, which involved both the organic and the inorganic matter from their surrounding environments. The Maya peoples even believed this presence (which they termed a “life force”) to stem from a ceiba, or tree of life system. In this system, human sacrifice was necessary in order to appease and replenish the Maya connection with and sustainment from their life force. Additionally, due to the supposed vital role of the life force, the Maya peoples utilized the technique of animism through line incision in their artwork. An excellent example of that artistic practice is a carved panel from the South Ballcourt at El Tajin (Late Classic Period). Those artistic choices made in the carved panel work together to depict just how inherent the Maya belief system was, culturally. I found all this information interesting along many lines of thought. To begin, it is striking how many of these same concepts are still being recycled in today’s science.

While current experimental study does not support the concept of a creating deity, it does still consider how humans and their surroundings are interconnected biologically and evolutionarily. This also, of course, spills over into religious or ethical ground when those same humans in society question what implications that biological interconnection (or ancestral relation) might have on humanity. I chose, much like the Maya civilization, to speculate on this interconnection and its consequences through first an animistic discussion and through also the incision of information into a surface. My art history for the semester is predominately inserted in those two ways on several pieces. To begin, I utilized the practice of animism in respect to the fruit and tree stump of Probability, a piece discussing the interaction of generations. This technique helps seamlessly connect the organic metaphor of life cycles (fruit to human). I find animism to be a comfortable way to both transfer simile into metaphor and to personify a piece, making it instantly more relatable to a human audience. Secondly, the technique of incising line (to indicate space and form) is far more overwhelmingly evidenced in my work. After exploring this technique on several pieces throughout the semester, I cultivated the skill set as a quick avenue that delicately communicates information. That information in this case is specifically the cycling beliefs due to one’s history or culture. Furthermore, this information (through carved imagery) is indicated in such a shallow manner that the artist is then capable to work along different levels or planes of consideration, setting up alternate, interesting angles of commentary throughout the work. This comparison (of form vs. line) is obvious in the work in consideration here. The imagery in All Tied Up is elevated on a distinctly shallow, separate level, allowing the subject matter of apples to nearly disappear as an afterthought into the background. Altogether, while the Maya ideas are millennia old, they have still proven to be a fresh way of inserting information into my work this semester. This Mesoamerican study has enriched both my work and my thinking process, as it did theirs.

Josh Novak

The Coatlique and Jaina Island Figurines

The Aztec Coatilque and the Mayan Jaina Island figures are two contrasting sculptures not only in religious cultural beliefs but in formal elements as well. I chose both of these figures because I found them to be both aesthetically pleasing but also a direct contrast of one another.

The Aztec Coatlique, 8.9 ft tall, carved out of andesite stone, is the representation of the goddess, Teteoinan “The Mother of Gods”. According to the Aztecs she is the creator of all of the other deities that they worship, but she also is a destroyer, because she is also the mother of mortals as well. She is depicted with the head of two serpents due to the legend that she was decapitated and two serpents sprung up from her neck. She wears necklace of human hearts, hands, and a skull relating to the fact that she feeds on the dead, as the earth consumes all that dies. Her skirt is interwoven with serpents, which represent fertility. The sculpture itself is massive and violent, the geometric, hard-edged shape adds to the robustness of the figure. It is difficult to see that the figure is even a woman. The monstrous head of the figure followed by the human remains beseeched across her used flabby breasts, due to her raising all of the other gods, is riddled with symbolism. This Goddess in all of her violence and beauty is a prime example of belief system of the Aztecs. If their Goddess is this violent, she is given power by feeding the dead, and she herself was decapitated. It fostered the strong beliefs of human sacrifice and brutal warfare that was so eminent in the Aztec culture.

Stepping away from all of the violence of the Aztecs, one could draw their attention to the Jaina Island figurines to the South. By the subtle features, and realistic expressions that each one possess. Though it is difficult to decipher whom the figures are supposed to represent. It does however give us a greater understanding of the dress, style, and physical adornments of the Mayan culture. There are three phases of development in the Jaina Island figures: Phase I has figures which are delicately detailed and naturalistic and often regarded as the best figures of the Americas, spans from about 600 AD to 800AD, Phase II is known more for its figurines created out of molds which are then enhanced by coils or subtle details, and the last phase, known as the Campeche Phase, the figures are casted entirely out of molds and there is a focus on an idealized figure of a woman, more than a individual. These sculptures served a purpose in the burial ritual of the dead. The extent to their purpose in the burial ritual is unknown. The figurines are paired randomly it seems, when placing the figurines with either males or females, there is no exception between the two. In reflection of these two similar, in terms of geography, yet very different cultures are important in the understanding of the Pre-Columbian belief system and cultural customs. These two figures represent two very different views on man in terms of the afterlife.

Africa

Katy Jones

The Great Mosque of Djenné

The Great Mosque of Djenné is considered to be one of the largest if not the largest structure built using mud brick or adobe. (Beautifulmosques.com) This mosque in the city of Djenné in the country of Mali, is reported to have been built in the 13th century, however, the current structures dates back more to around 1907. (Beautifulmosques.com) In 1988 The Great Mosque of Djenné was also determined to be a World Heritage Site by UNESCO. (Beautifulmosques.com) The use of the mud brick made it so that in such a hot climate, the mosque would heat slowly due to the consistency of the adobe. (Beautifulmosques.com) This mosque, shows the incorporation of Islamic architecture into design, as well as indigenous materials to the region. (Beautifulmosques.com) The Djenné mosque was also where many people from Western Africa would come to worship and learn more about their faith since it was a large mosque many would make pilgrimages there. (Sacredsites.com) The reason that there still is exterior scaffolding is due to the fact that it is necessary for the workers each spring, when they restore the plaster to the exterior of the structure during a yearly festival. (Sacredsites.com) This festival is a way to engage the youth in the community to take an interest in this historical site as well as being able to preserve it. (Sacredsites.com)

I found this mosque to be interesting due to fact that it has been so well kept for since it was built in the 13th century. The structure itself also holds a lot of intrigue as well due to the fact that it holds Islamic influence. I have always found it interesting how the religions spread throughout the regions when there wasn’t such a division of countries as we have today. The walls of the mosque are so high due to the nature of the mud clay, the only way that it could support itself is if the walls were built high enough to create strength within the walls. I also was attracted to this structure after researching it more because I found out that it was tradition for those that live in the town to restore it every year. This interested me due to fact that they have taken such an interest in keep such a piece of history in good condition and that they have so much pride in having a World Historical Site.

Debi Cox

African Pottery- Coil Formed with Slips

The piece is an example provided by L. Ganstrom through our class powerpoint depicting African Art. This piece reflects the work of the past- of many cultures that learned techniques from one another as the concept of copying is a rather new thought process and I’ve been studying Greek pottery this semester as well. I’m amazed that the same similar look can be achieved in various ways, some being fired only once and burnished at the leather hard stage, and others being fired twice and burnished after bisque. Some were dung fired and others were fired in kilns. None the less, this piece is African pottery. African pottery began around the 7th century BC and continues today throughout Africa. This pottery has always been created by women. Most of the work was for utilitarian purposes such as cooking storage and collecting water etc.(2) African pottery was formed by hand using one of the following methods of building. The techniques used include the concave mold, convex mold, direct pull, coiling, and hammer and anvil techniques. (1) Coiling was the primary way of forming these voluptuous forms. A beautiful example of this traditional process is provided on you tube at the link below. http://youtu.be/EyeUNaWWpgw

The African pots were all formed by hand which created a fragile, heavy finished product. They were fired in a pile stacked carefully, then wood, dung and other flammable material was place on the surface for firing. They were polished after being fired. The women would display their amazing dexterity skills by hand building many large vessels, using slips and other materials such as vegetable juice for color. They were built by hand. The vessels were fired at a low temperature.(2) The National Museum of African art in Washington DC houses “140 ceramic works from different regions of the continent. Among the most important are a group of 85 vessels from Central Africa. A few of these pieces are displayed along with other traditional works, including a beer container from the Chewa peoples of Malawi, a water vessel from the Yoruba of Nigeria, and water and oil containers from the Berber of Algeria”(3)

Work made as it was thousands of years ago keeps this aesthetic alive today. Although the work made in this manner today is not thought to be utilitarian, the technique remains popular. A quote about Magdalene Oduno, artist born in Nairobi that resonates with me is this:”There is a paradox for a current potter like Magdalene making containers destined to remain empty when the references are manly ceramics from the past, which were utilitarian.”(5) 1–https://www.createspace.com/204744 2–www.all-about-african-art.com 3 http://africa.si.edu/exhibits/ceramics.htm 4–http://www.nature.com/news/pottery-shards-put-a-date-on-africa-s-dairying-1.10863 5—Barrel, Pit and Saggar Firing—Articles from Ceramics Monthly

*A fun but totally non related fact about African pottery came about in my research and I thought I would share it…………… Yogurt may have made it on to the menu for North Africans around 7,000 years ago, according to an analysis of pottery shards published today in Nature(4)

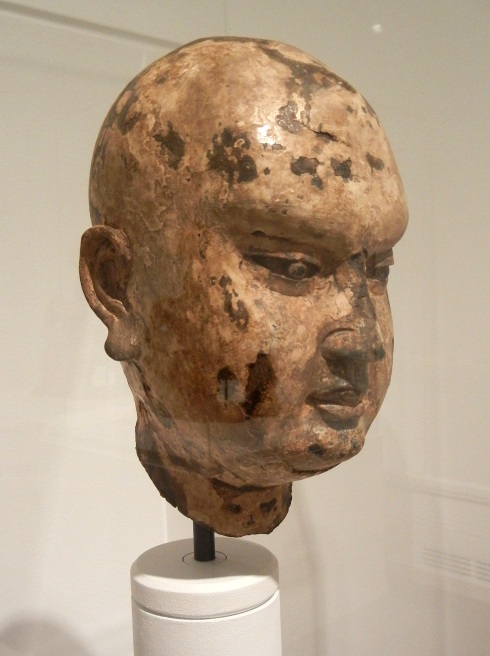

Kingdom of Ife, Terra cotta sculptures from West Africa

During the first decade of the 20th century, Picasso and Matisse introduced the Western world to what they thought was the essence of Africa. The African masks that influenced works like Les Demoiselles D’Avignon (1909) seemed to be Picasso’s interpretation of what ‘primitive’ art was: pure art, not influenced by greed and the progress that ‘modern’ industrial society had made. As well meant as Picasso’s opinion may have been, it is somewhat of a patronizing thought of the West to conclude the style to a whole continent; because there are so many Africas and there is so much more to African art.

Here is one example:

What is today South-Western Nigeria, once was called Ife; the walled city-state of Ife, the legendary homeland of the Yoruba, a culture that flourished for about 300 years from 1100 to 1400 AD. In 1910, the first major excavations took place there, and thirty years later, in 1940 a second round of anthropological digs happened, which resulted in large headlines in London Newspapers: “….worthy to rank with finest works in Greece and Italy.”

At the same time that High Renaissance hit Europe, anonymous artists in Ife were working with terra cotta, copper and brass – long before the Europeans had arrived there! The resulting artwork, a series of the most brilliantly executed clay and bronze human heads, is as refined as Donatello’s work and as naturalistic. We know that the terra cotta work was done by the women, and that the men worked in metal and stone.

No written records exist from this culture. However, what art historians conclude from the refined works of art, is that it was created by people of a very advanced culture.

A typical Ife head is life-size. What strikes the viewer first is the perfect naturalistic depiction of a human head, simplistic, clean, with a smooth surface and a serene expression. The faces show a tight net of vertical striations, possibly depicting skin decorations from scaring. We see full lips, prominent cheek bones and eye brows. All the heads are said to depict real people, possibly rulers or other important figures in society. The head dresses are either tiered or pillbox-shaped or consist of a series of delicately carved beads, built up in concentric rings.

Since art historians originally associated the work in its quality to artwork found in Greece, the theory of Atlantis was discussed in connection with the finds of the Ife heads. However, whole body figures that were found in Ife as well did not reflect Greek proportions. Therefore, it was concluded that the Ife culture was a truly African tradition that resulted in the fact that even the Africans themselves had to re-think their own history.

Kelly McComas

Prehistoric African Art

Art in the African culture as with other societies portrays those of higher places in that society. From kings to whom they represent in the family or the community the art also displays moral behaviors that the people of that society must live by. Around the 15th century the Europeans explored Africa and have taken much of the prehistoric artworks back to western museums. It was only until the end of the nineteenth century that people came to admire the primitive qualities of the art and through more recent time’s people have been doing more research to understand the meaning from the artist’s point of view.

African art is known to have started in the Pal eolithic era from paintings and etchings in caves. Through the years as agriculture developed in Sudan early knowledge of iron work came in around 3000bc .It is believed that the technology of the ironworks came from a tribe known as the Nok s. The Noks were mostly farmers and smelters and used this technology to refine ore. In fact the earliest known sculpture of sub Saharan Africa is from the Noks making terra cotta human and animal figures.

The sculpture made from Terra Cotta of the Nok head is from Nigeria dating back to 500 BCE-200CE. It is thought to come from a full sculpture figure and it is not exactly known what they were used for or their meaning this is why these sculptures were never excavated. The sculpture has the D-shaped eyes of the Nok which was like those of the animal figures they created as well. The buns in the somewhat stylish hair style had holes in them in which they could hold feathers, beads and other ornaments.

What I like most of this sculpture is the strength the face portrays. it seems like it could be a sculpture of a man but it also could be a woman as well. The sculpture draws the imagination in with its large hollow eyes and expression. It does lead me to wonder who this person may have been and what their status was in the tribe. I find it amazing how well preserved it is for its age and that it would be so unique if in fact the rest of the sculpture was intact.

Michaela Valli Groeblacher

Ancient African Functional Ceramics

In an article titled The Inescapable, Indivisible Essence of Pottery, Warren Frederick asks the question of how can objects that were created in earlier epochs, from our own or other cultures, touch us so deeply? Can pottery whose origins spring from foreign cultures or distant times actually be germane today? In addition, another question arises: How are, in a time when technology seemingly obliterates the necessity of the hands-on making of objects, these objects still relevant and – for us as teachers of this ancient hands-on craft, are we still justified to continue passing it along to younger people?

Pottery’s potency lies in its resolution of dual realities: obviously, there is the sphere of physical use: the realms of filling, pouring, carrying, or perhaps brewing; then there is the sphere of abstract use: the figurative realms of sustenance offerings, status, emotional containers, or burial accessories within a given culture. For pottery this duality of abstract and physical use confers both irreplaceability—no other medium can take its place—and indivisibility—the utilitarian, spiritual, and aesthetic are forever intertwined. Yet pottery’s essential utilitarian character can cloak the abstract essence through which these African vessels serve the soul. In Western cultures that have separated art from daily life, the seam of this duality is prone to being ripped apart. (4) Today, we cannot experience these objects in their original contexts any longer. As objects leave their place of origin—whether yesterday, one hundred, or five thousand years ago—they begin to lose specific traits. It is forgotten who made them, when they were made, how they were used.(4) Yet the art remains extraordinary and compelling. (4) As we look at it, we try to envision glimpses of each story; we learn about other times and places and we interweave our own experiences and relationships into that dialog. Our common humanity explains both our need and our ability to draw insights from the creations of others.

Art is always moving away from its origins, suffering an inevitable loss of context. (4) Early art that is as articulate as ancient African pots, speaks to us because it is attuned to current necessities. Those vessels convey a fundamental sense of earthiness and immediacy. They embody nature as they also manipulate nature. The unadorned qualities of clay and earth are embraced. Earthenware, when it is handled “naturally” and fired what we Western ceramicists call “alternatively’, is not overwhelmed with thick, colored, and seductive glazes that high-fired wares are very often. Incorporated in these African vessels is a unified spirit of spontaneity and assurance, whether rough and unrefined or elegant and vigorous.

Vessels are not transparent windows into the past, but membranes that express their own properties and qualities. For an artist, historical pots are a contemporary reservoir of inspiration. They enlarge the vocabulary of a common ceramic language and enable new methods of combination and communication. Handmade artistic objects, each vessel remains unique and alive, bridging time and geography. The eloquence of the hands, eyes, and hearts that made these objects still captures our passion. In using such words as lip, neck, shoulder, belly to describe the shape of a pot we acknowledge its likeness to a living thing. (8) Pots reflect not only universal human character traits—anguish as well as vigor—but also the diverse shapes and protrusions of the human body. As a metaphor for the human body and as an object typically sized to fit our hands, pottery is a close, manipulable presence. (4) The ornamentation is not an addition or an afterthought, but an indivisible component of completion and fulfillment. (7) If we conceptualize pottery surface as skin, and African earthenware pots certainly invite to that, we can convey the essentialness of surface markings. Skin is indispensable to life, the central mediator between our internal nature and the external natural environment. Treatments to each vessel’s skin are integral to these forms. Even when symbolically unfathomable, these clay skins are reminiscent of body markings, wood carvings, textiles, braided ropes, and animate creatures. Touch is inescapably vital for experiencing all pottery because of the centrality of its use. Interaction transforms both the object and us. Unexpectedness—an unanticipated double neck, an unusual shaping of a shoulder or foot, looped handles that seize exterior volume, or a convoluted yet coherent patterning, keeps us fascinated. To call these pieces “primitive” negatively connotes simpleness and backwardness emanating from cultural arrogance. (9) If we would do so, it is our ignorance of the abstract sphere of pottery that is unsophisticated, not the objects themselves.

Bibliography 1. Ellen Dissanayake, Homo Aestheticus: Where Art Comes From and Why (New York: The Free Press, 1992).. 2. Ellen Dissanayke, “Very Like Art: Self-Taught Art from an Ethological Perspective,” in Self-Taught Art: The Cultural and Aesthetics of American Vernacular Art ed. Charles Russell (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2001). 3. Warren Frederick, “The Poetic in Primitive Pottery” in Ceramics: Art and Perception, 20 (1995), 4. Warren Frederick “The Inescapable, Indivisible Essence of Pottery” 5. Frank Jolles, “Zulu Beer Vessels,” in Tracing the Rainbow: Art and Life in Southern Africa, ed. Stefan Eisenhofer (Stuttgart: Arnoldsche). 6. George Kubler, The Shape of Time: Remarks on the History of Things (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1962), 33. 7. Kubler, The Art and Architecture of Ancient America, 3rd ed. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1990). 8. Arthur Lane, Style in Pottery (London: Oxford University Press, 1948). 9. Sally Price, Primitive Art in Civilized Places (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989), 10. Philip Rawson, Ceramics (London: Oxford University Press, 1971).

Spring 2012 Research

Asia

Ned Day

Ancient Chinese Ceramic History “The ‘Jian ware” or “Chien ware’ Tea Bowl”

The modest tea bowl holds a special place amongst the many famous forms of ancient Chinese ceramics. One of the specific types of these tea bowls is called “Jian ware” or “Chien ware” for its location in the Fukien province of China. They were first fired in the kilns at Jian’an and later at Jianyang and was mainly produced from 960 to 1279 CE during the Sung dynasty on up to the early 14th century in China. While “Jian ware” or “Chien ware” was not limited to the tea bowl form, it was its most common. They varied from large to small, yet most are in the 3 to 5 inch range. They were used by Chan (Zen) Buddhist monks of the region. The tea bowls were highly regarded by visiting Japanese monks who had come to study Chan Buddhism and were carried back to Japan. There in Japan the “Jian ware” or “Chien ware” was termed Ten-moku or Temmoko. The term derived from the Japanese expression “T’ien Mu Shan” (Mountain of the Eye of Heaven). This was the location of a monastery in Chekiang province of China where a tea ritual was performed using Chien bowls. This type of ware became the type of tea bowl preferred for the highly ritualized Japanese tea ceremony into the late 16th century. One drawback to the name Temmoku is that it was also used to describe works made in the provinces of Hopei and Honan of North China. These were made using white clay bodies and only have a superficial resemblance to “Jian ware” or “Chien ware”. “Jian ware,” “Chien ware” or Temmoko is dark brown or blackish glazed Chinese stoneware originally made for domestic use. It was a peasant ceramic. Yet, it is a dense, high-fired stoneware unlike any other. The body is dense and the glaze thick. Its dark coarse body was made from a common clay that was not blended or screened. The down-side of these bowls is the rough rim. Because of the flow during firing of the runny glaze, the rim is almost bare. It is also rough because the glaze corrodes the coarse clay body leaving the larger particles more exposed at the surface. Although material to make this clay body most likely exists world wide, it is not available commercially today because there is no other application for it. Similar clay bodies have been formed using a coarse fire clay and adding an iron-rich material. The glaze is not any more complex than the body. In Robert Tichane’s book, Celadon Blues, he describes accurately replicating the glaze with a simple combination of red clay and wood ash. This creates the dark brown to black color with iridescent blues. This replication examined with a microscopic and x-ray has the same appearance and pattern as the original glaze. The ware had a range of variations within a limited palette. Streaking and iridescent patches were formed on the glaze resulting in specific names such as Oil Spot, Hare’s Fur, Partridge Feather, Tea Dust, Khaki, Yohen and other variations. Of these effects Oil Spot and Hare’s Fur were the most prized. The different glaze effects resulted from slight differences in raw materials, as well as time, temperature and atmosphere in the careful control of the kiln firings. Due to the high iron content of the body, firing was most likely done in oxidation otherwise the body iron would have slumped. Also, the firing must have been taken to high temperatures between cone 8 to cone12 to make the body dense and create glaze running which dripped off the outside of the bowls and pooled in the inside bottom. While the glaze appears to be dark brown or black on the dark clay body, a chip of this glaze placed against a white background has been discovered to be amber.

There are several basic forms of the tea bowls of “Jian ware” or “Chien ware.” One of these forms is considered a classic of the region as well as originally unique to the location. This style is designed with a groove close to the rim to provide an area to grip with fingers. Another clever feature is a sharply beveled shoulder near the base. This abrupt angle is purposeful in collecting the runny glaze in the form of drips and rolls. This angle also prevents the glaze from flowing down to the foot. When glazed, the bowls were dipped only so far as to not go past this angle. Due to their thoughtful and purposeful design, link to the ritual of enjoying life and pleasing glaze effects, these tea bowls are still highly valued and replicated today.

The Han Dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE) was the second imperial dynasty of China. Architecture was very important during this period. The gateways, city walls, complexes etc all were built to show power, prestige and provide defense. Many of these miniature buildings were placed in tombs for use in the afterlife. The Han Dynasty was an age of economic prosperity and saw a significant growth of the money economy. The mini mansions represented to social ranking and status of the individual buried there. They also represented an improvement to the building of the time.

These forms were made of red earthenware and green soft-bodied lead-glaze wares. They were manufactured largely in central China. The models were made up of multiple detachable sections which together form several levels. Although nearly two thousand years old, they clearly show the tile roofs and cantilever bracket system in some cases, and deep overhangs and walled courtyard that have remained standard in traditional Chinese architecture today. This basic system of multi-story construction was later adapted to the building of Buddhist pagodas.

While soft-bodied lead-glazed wares were manufactured largely in central China, the coastal region of southern China continued the production of high-fired stoneware incorporating a wood or ash glaze with a yellow-green color range that can be considered an early form of celadon. Several other ware types were represented in the Han period. They included painted grey ware (imitated lacquer ware), burnished black ware, and stamped and incised decoration both glazed and unglazed. Some of the buildings were watchtowers, made to protect, some were prestigious homes, other structures were viewing towers for the wealthy and elite. They never had a purpose above ground and were only used underground in tombs and made to accompany the deceased to the afterlife and to provide comfort in their surroundings.

Deb Cox

http://www.artsmia.org/viewer/detail.php?id=3760&i=6&v=2&class=ceramic&op=1193

http://www.historum.com/asian-history/27758-han-dynasty-architecture-2.html

http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/works-of-art/1984Title:Funerary Model of a Pavilion.397

http://www.artsmia.org/art-of-asia/explore/explore-collection-architectural-models-interview.cfm

Sancai Tomb Guardians of the Tang Dynasty

The Zhenmushou is a “tomb guardian” or “earth spirit” from the Tang Dynasty, (618-907), in China. These burial pieces were called Ming chi or “spirit objects.” The Zhenmushou figures were meant to scare off grave robbers as well as transport the deceased to their new realm with at least the same prestige that they experienced on earth. It is also said to keep the spirit from traveling aimlessly. The Chinese believed that the next world was a continuation of this world. This Zhenmushou piece is quite large. It is 41.75 inches tall. These fantastical figures guarded tombs from the sixth through eighth centuries A.D. They generally guarded the entrance of the tomb as a pair; one on each side of the entrance.

This earthenware Zhenmushou has a humoresque face with human and animal characteristics. The face is part human, part ogre and part beast. The beast’s mane is fashioned with feathering flames waving on top of his head. His ogre-like ears bloom like flowers from the side of his head. He wears a grimacing smirk on his face. The head is left unglazed with a post-fired pigment added. The body is glazed with a classic leaded Sancai glaze on the body.

The characteristic of the Sancai glaze bleeds and runs over the red, black and orange slip.

The body is a morph of animal images. The creature’s chest protrudes with a cream colored stripe down the center. His chest and cloven hooves are like a deer, but its hind haunches are more dog-like. The beast has what looks like fins and wings emerging from his shoulders which have a green glaze. The green glaze stripes his legs and his back quarters. The figure sets on top of a rock base that has holes in it.

The tomb guardians range from warriors, beautiful Tang women of high society, animals, musicians and mystical beasts.

These figures give us a little insight into the Chinese funerary methods. The figures may have represented some auspicious omen and might well be tied to Chinese mythology or Buddhist deities. This composite creature were meant to be scary tomb guardians. These tomb guardians were not originally meant to be viewed as art. As the railway ran though China and disturbed the ancient Tang Dynasty burial sites, they became beautiful, coveted sculptures.

Sharon McCoy

Ceramics of the Ancient European World

Fall 2011

Richard Dillard

Greek life on plates

Through time, many different creations have come and gone. The Greeks tried to trap that in their work, of how everything, not just certain things had to have reasoning behind their creations. They made red on black plates with images of everyday life permanently engraved in them. Some of these images were often bath houses, gladiators, The Gods, or other things that they saw or believed in on a regular basis. Most women weren’t always the artists like in many other cultures; men played a large role in this process. As for pottery, the Greeks developed the first kick wheel. This kick wheel had to be run by two or more people and it was the thrown to coil method. The largest vases could have been up to 9ft. tall. Most of the pottery that the Greeks had often made was just for storage. We now know however that most food or product would not be safe to eat if stored in a porous container due to the fact that food could be stuck in the pores and give us a disease or infection. Greeks always tried to keep the figures of man and woman exact. So that way there would be no confusion towards questioning them. When they made a creature or mythical creature, it was blown out of proportion, the lion would have gigantic teeth and the Minotaur would have large horns.

Ned Day

Greek ‘red-figure’ pottery was was developed in the city state of Athens in the sixth century B.C., and lasted to the third century B.C. It marked the height of the development of Greek pottery decoration. The development was influenced from a long history of innovations from both Athens, other Greek city states and Asia Minor. These decorative innovations began in the eleventh century B.C. This was after the decline of the Minoan palace culture of Crete and its economic influence in the twelfth century B.C on Mycenaean Greece. This lead to decline in Greek culture and population known as the Greek dark ages. This period

is characterized by its lack of sophisticated arts such as elaborately decorated pottery.

The eleventh-century resurgence of the Greek city states began to develop especially in the region of Attica with Athens as its epicenter. Here is were the skill of the craftsman becomes paramount in the surface decoration of pottery. Where at the end of the Mycenaean era floral patterns were simplified to roughly drawn concentric arcs and dots. Athenian pottery decorators of the eleventh century began to use innovative techniques such as multiple brushes attached to a compass-like device to produce more exact concentric circles and semicircles. This period is known as the ‘protogeometric’ period. Also at this period firing methods were improved to create more rich and regular gloss blacks on the surface design. The bold, simple patterns of the ‘protogeometric’ period lasted until around 900 B.C. From this point the patterns started to become more complex, intricate and varied. Known as the ‘geometric’ period, it also originated in Athens. This ‘geometric’ period is thought to have been inspired by domestic crafts of the time such as wickerwork and weaving. Near the middle of this two-hundred year period, 800 B.C., animals and human figures became incorporated into the geometric patterns by way of panels or friezes. These were either burial or battle scenes, and they served as grave markers. Monumental in purpose, they were larger in scale compared to their purely geometric counter-parts that served domestic utility.

The use of animals and figures began to gradually displace geometric pattern in the 700s B.C. This began in the eastern Greek city states of Asia Minor as they conducted trade with neighboring regions such as Syria and Phoenicia. These eastern decoration motifs on bronze and ivory wares eventually spread across the rest of the Greek city states through trade as well. This influential period lead to what is called the ‘orientalizing’ style. Not only were the mythological creatures and heros borrowed, but also the technique of incising. This allowed for far greater detail than brushwork to create more exact individual identities of figures.

When the‘orientalizing’ style reached the city-state Corinth it was eventually adapted to a more graphic representation of the human figure and some animals. It became what is referred to as ‘black-figure’ pottery. This was in-turn exported and became influential throughout Greece. This style remained dominate through the late 600s B.C. to the early 400s B.C. Although the incised ‘black-figure’ pottery would remain dominate for some time to come, in Athens a new technique started to develop around

525 B.C.

In this new technique the look was completely reversed. The background appeared to recede as it was painted with black slip and figures visually came forward by being left the natural warm red of the clay body. Greater line control with brushes lead to the eventual end of the incising technique on ‘red-figure’ pottery. With its distinctive difference from ‘black-figure’ pottery of Corinth, it lead to great exportation of pottery from Athens. ‘Red-figure’ pottery continued to develop with more fluid lines, a heightened sense of anatomy and three-quarter profiles. This lead to it becoming a more naturalistic style, which later dominated the two styles. The beginning to the the third century B.C. marked the end for ‘red-figure’ pottery. This was the beginning of the ‘Hellenistic’ period and simpler decorated wares became favorable. From its emergence to its height, ancient Greek pottery reached many achievements in form, composition, naturalism and craft.

Kayla Hern. Minoan Ceramics

Since the beginning of time there has always been some form of art present within the different periods of time. From paintings on the walls of caves, to ancient forms of pottery found in Pharos tombs are all part of the artistic history of the world. The most influential art that really captivates my attention is Minoan pottery.

The Minoan era of pottery had evolved over the years of 3000BC-1100BC. This was known as the Minoan time period, from early to late Minoan. Over these decades their pottery flourished to great extremes. The Minoans art was created and even found within the island of Crete, which is in Greece (History of Crete). They set up their villages and started to prosper, when the Minoans eventually took to trading on the sea. Their pottery was traded with the surrounding areas such as Africa, Asia Minor, and even Egypt along with a few others. From this point on they were able to spread their artistic skills of pottery to other nations and civilizations.

Larnax (chest-shaped coffin), mid-13th century b.c.;

Late Minoan IIIB, Minoan; Greece, Crete, Terracotta (Minoan Crete)

Throughout the decades that the Minoans created fabulous pottery that is still being admired today. There are many different techniques that they used to acquire such beautiful creations. For example they enjoyed painting in naturalistic objects like octopuses, people, other animals. Not only did they just paint those objects on the pottery but they also do very geometric designs on them as well. They soared to new heights when they started to create other colors with their varnishes. (Material and Techniques). They would also create their different forms of pottery by burnishing their pots with a stone to make the surface a smooth and shinny. They also created later on different pottery with human figures etched into the surface of the pots. For example the vessel below is a great one to talk abut.

Hagia Triada. Crete. Harvester Vase. c.1550-1500 BC

This vessel is very interesting to admire because if you thought it was a ceramic vessel you are wrong it is actually a stone vessel (Minoan Civilization). In fact the Minoans did not only create ceramic pottery they also worked with stonework as well and created functional pottery (Minoan Civilization). With using the stone method of pottery the Minoans could create a vessel with carving in the surface. In my own opinion I believe that the ceramic vessels are not only more colorful but more decorative as well. They are so interesting to admire because it is almost as if each pot is telling us a story of the past. For instance the vessels with octopuses on them are obviously showing us that they have knowledge of the sea. If there was not a sea by them, then they probably would have never known what an octopuses looks like. So they also can tell us a little bit about their history as well.

Without the knowledge ancient civilizations, we would not be were we are today with all of the different pottery techniques. Because of the past artist of the Minoans, we have learned great ideas and knowledge from their styles of work that they accomplished. The Minoans pottery has had a great influence on all of the other potters throughout the different centuries.

Amphora with three handles with Marine Style decoration.

Late Helladic IIA. c.1415. Covered with glaze paint.

References

“Material and Techniques of the Minoan Ceramics of Thera and Crete — The TheraFoundation.” Frontpage — The Thera Foundation. Web. 23 Nov. 2011. <http://www.therafoundation.org/articles/technology/materialandtechniquesofteminoanceramicsoftheraandcrete>.

“History of the Island of Crete in Greece.” History of Crete. Web. 23 Nov. 2011. <http://www.interkriti.org/crete/history_of_crete.html>.

“The Minoan Civilization (2600-1200 BC).” Ancient Greek Thesaurus. Web. 23 Nov. 2011. <http://www.greek-thesaurus.gr/Minoan-civilization.html>.

“Minoan Crete | Thematic Essay | Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History | The Metropolitan Museum of Art.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art – Home. Web. 23 Nov. 2011. <http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/mino/hd_mino.htm>.

“Minoan Crete | Thematic Essay | Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History | The Metropolitan Museum of Art.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art – Home. Web. 23 Nov. 2011. <http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/mino/hd_mino.htm>.

Sharon McCoy

The Etruscan Sarcophagi of Seinti Hanunia Tlesnasa

Like many civilizations that no longer exist, we have proof of their existence by the artifacts that remain. This is true about the Etruscan culture in the mid second century and later. Archeologists have found tombs and funerary remains from the Etruscan community in an area between Pisa and Florence, Italy. Along with these remains, they found several sarcophagi which are above ground burial crypts. Some of the sarcophagi are made of stone and some are formed from the indigenous terra-cotta clay.

The terra-cotta clay sarcophagus was made only for the wealthy. We know that because ere were simple sarcophagi like this particular Seianti family sarcophagus that displays the portrait of the woman’s whose remains are inside the sarcophagus. Inside the Seianti sarcophagus, archeologists found one of the most well preserved skeletal remains of the Etruscan period. Scientific explorers rebuilt a model from her remains to determine what Seianti Hanunia Tlesnasa might have looked like. The model bore a striking resemblance to the portrait on the lid of the sarcophagus. Yet, the model was an older version and probably a little more robust.

We know who Seianti was because there was an inscription with her name and the family name on the base of the box. All of the terra-cotta Etruscan sarcophagi were brightly painted. In this one, the woman was seated in a reclining position with her left arm propped on a pillow holding a mirror. With her right arm, she is pulling her white veil away as a woman would do in a wedding, In the wedding thus symbolizing that she is a married woman. The noble woman has many layers of clothing. Her Hellenistic dress drapes over her body in an undulating flow. The gown is embellished with blue borders. The reclining figure also has a white cloak with red borders and a blue salvage lays over her legs. Her gold girdle is around her mid section.

A visual reference to her community stature and wealth is how the figure is lavished with jewelry. She wears a double serpent bracelet on her right forearm and several rings on her hand. Her disk earring hangs with a cone shaped drop. Around her neck, she has several pendants on her necklace. On her left arm, she wears another bracelet. All of these fineries are painted with gold. This adornment was a statement that Sieanti Haununia Tlesnana was a woman of noble rank.

The side of the sarcophagus is decorated with rosettes and Corinthian columns.

There are other sarcophagi as elaborately built, and some with reclining couples on couches with legs. Still, others have more of a resemblance to a cruder Kouros figure, but this one seems to be preserved the best–albeit not the oldest. These large terra-cotta sculptures pay homage to their occupants and give us tremendous insight into a previous culture.

The Minoan Snake Goddess

Tricha Wiese

Art historians have long speculated about the reasons behind the Minoan culture’s lack of the traditional types of architecture and artifacts that usually serve to immortalize a hierarchical ruling class. There are remains of large palaces onCretedating to the Minoan era, but these remains are lacking in monumental sculpture depicting specific gods or individuals from a dynasty or elite class of clergy. Instead, the primary importance of these palaces seems to have been as a site to hold communal rituals and as storage facilities for the harvest. The walls of these palaces are decorated with murals depicting both the natural world and rituals such as an athletic competition involving leaping over a bull, and the spaces below these palaces contain complicated labyrinths in which rituals were performed. However, the lack of monumental sculpture is unusual for a Mediterranean civilization which displays the level of sophistication needed to produce the murals and pottery it produced and build the large, complex palaces that remain.

This absence heightens all the interesting qualities of the Minoan Snake Goddess figure, and leaves questions about it unanswered. The size of these figures is small, only about thirteen inches in height, and they are usually found in a prominent niche in domestic dwellings rather than in public settings. They are made of faience, which is ground quartz mixed with other minerals and fired. This gives these figures a jewel-like quality and the use of this material is believed to be symbolic in ancient times of the cycle of life and death. The dress of the figure is complex and sophisticated, which also reflects the sophistication of the culture. The skirt is made of multiple tiers, the apron and bodice are quite ornamental, and the figure is also wearing a headdress. The bodice is open, leaving the breasts exposed, and she is holding two snakes in her outstretched arms. A cat-like creature is perched on top of her headdress.

These features raise questions about whether the Minoan Snake Goddess is a fertility deity or a priestess. The exposed breasts and association of snakes with earth, water and the renewal of life could suggest fertility deity. Also in line with the deity theory is that these figures are stylized depictions of a concept rather than portraits of specific women. However, the sophistication of the costume and jewel-like quality of the materials often used suggest these figures are priestesses, and the depiction of the figure in the act of holding out the snakes suggests she is performing a ritual. If these figures are meant to represent priestesses, however, it is interesting that none exist as specific portraits or monumental public sculpture. What is clear about these figures is that their placement in a prominent area of the Minoan domestic dwelling indicates they were a significant part of the religious life of the Minoan people, but that sustaining its significant to the culture did not seem to require a massive public work of its likeness.

Kyndsay Starkey

Minoan art flourished during the Prehistoric times in Crete. The Minoan culture existed from 2600 BC to 1500 BC, after the legendary King Minos.The ancient Greek civilization in Crete has provided us with some of the earliest known examples of ancient Greek art. Minoans were seafaring traders with a large Palace at Knossos, which was discovered and researched by the early Sir Arthur Evans in 1900. Very little sculpture had survived from Minoan Crete, because most of the sculptures were not monumental. Most of the sculptures seemed to be smaller artifacts that were dedicated to kings and gods. One of the best known examples from the Minoan Crete area is the Snake Goddess.

This ceramic sculpture goddess represents an ancient fertility goddess. She was found in a storage room in the Palace of Knossos, Crete. She was found broken into many pieces. One arm, the head, and parts of her skirt were missing. The missing pieces were reconstructed according to the artists imagination of how the original pieces looked. This figurine is a personification of Earth from which all life springs and returns. The snakes that she is carrying represent death and rebirth. The lion cub that is crouched upon her crown is usually associated with royal houses. There are also poppy pods that are in her crown that are indicating the use of opium in her worship.

The Snake Goddess is about a foot tall. She is holding two live snakes in her arms that are held up high. This sculpture is made out of faience, a technical sophisticated tin-glazed pottery. The flesh seems to be a white color and the clothing is a variety of different browns and yellows.

According to a student from Drury University, “She may be a snake charmer, a priestess, a Goddess, a festival attendee, a dancing girl, all of the above or nothing that has ever been encountered before. However, it is her appointment of ‘Minoan Snake Goddess’ that is intriguing. This label has caused the biggest response among scholars, feminists, earth-based religious followers, and others today.”

John Hamilton

Made in 1500 BC, by the Late Minoan civilization, located in Greece on the island of Crete, these pots were made thin and called Kamares ware and completed in order to offer as trade for other items. These pieces were mainly painted using white, red and black paints that were then fired in a ceramic kiln. This Vase was decorated with the viewer in mind. The pattern (inspired by a floral style from the early Minoan culture) on the vase is repeated all around the piece enabling a visual movement from one side to the other continuously. Bands were placed on the top and bottom of the form in order to create a sense of visual weight and movement. The high contrast allows for the viewer to easily identify the marine content on the surface of the vessel.

(http://www.localhistories.org/minoan.html, http://humanitieslab.stanford.edu/ceramics/349, http://www.therafoundation.org/articles/technology/materialandtechniquesoftheminoanceramicsoftheraandcrete)

Renee Dreiling

The Minoan Octopus Jar

I absolutely love this piece of work. From the concept of the jar even to the way the use of the jar is depicted in the drawings on the body of the jar. The octopus shows a lot of movement on the jar. It looks as if it is about to jump right out at you off of the jar. The drawing of the octopus is also very naturalistic. In some ways it does have some abstractions, like with the size of the tentacles, but the scale that the body was drawn on is incorporated the same throughout the piece. The eyes of octopus are very descriptive and expressionistic. The octopus almost looks startled.

The Minoans used these jars to catch octopus from the Sea. The design of the jar allowed the hunters to catch the octopus efficiently without disturbing or distressing the catch. This octopus jar is many of its kind and was constructed around 1500 B.C.

Venus of Dolni Vestonice

Katrina Florell

When analyzing the artifacts that remain from past civilizations, it becomes difficult to understand the past function and value of the object within that culture. Early ceramic objects are also difficult to understand, but examining the evidence surrounding the artifact, some information can be established. One figurine, which has infinite importance, is the Venus of Dolni Vestonice. Through evaluating some of the evidence surrounding the object, a more concise understanding of the artifact can be established.

The Venus of Dolni Vestonice is the oldest known ceramic object in the world. [1] It dates to about circa 30,000 BCE.[2] The piece measures 4.4 inches in height and 1.7 inches in width and was made with the local clay fired at a low temperature of about 1300 degrees Fahrenheit.[3] This sculpture is among many other artifacts and Venus figurines found about the same period. It has many similar characteristics, for example, simplified features, exaggerated breasts, large buttocks, and hips.[4] The figurine also has a crack along the right hip and four holes in the top of the head.[5] Although there is speculation about the function of the holes, this is simply a theory. One piece of evidence is from a scan in 2004, in which a fingerprint was revealed on the surface of the figurine, it has been identified as being from a child in the age of 7-15 years.[6] It is not known whether the child was the creator of the object.

The Venus of Dolni Vestonice was found in a site near the modern day Czech Republic. It is believed to have been from the Upper Paleolithic Age.[7] This period is the last of the Paleolithic Periods and begins about 40,000 BCE, in Europe and ends around 12,000 BCE, more specifically when modern Homo sapiens were known to have existed. [8] These sites are referred to as the Gravettian sites (Gravettian culture or tool making culture, specifically small pointed blades for hunting)[9] or Dolní Vestonice (near the village of Dolní Vestonice.) They were discovered in 1922 and were first excavated during the first half of the 20th century.[10] The human remains found in the burials and charcoals recovered from hearths are radiocarbon dated to range between 31,383-30,869 BCE.[11] These sites provide the earliest evidence of ceramics, weaving, and what appears to be religious art in large quantity.[12] They have contained burials, objects and artifacts such as small figurines, shards, impressions of woven material, body decoration, like pierced seashells and wolf and Arctic fox teeth, and bodies that were sprinkled with red ochre.[13] Also found among the sites are hearths, a mammoth scapula, a lithic tool workshop, lithic tools, burial goods, stone tools, and possible structures.[14]

The Venus of Dolni Vestonice is often categorized and compared to the other Venus figurines discovered. These types of figurines have been found across a large area of Europe from Ukraine to France.[15] The “mother or earth-goddess” figure is most common type of female representation in the prehistoric periods but that does not suggest the Dolni Vestonice belongs to this category.[16] They have been viewed as fertility figures or “mother goddesses,” but more recently other purposes has been indicated for the function of these figurines. The representation of the life cycle of a reproductive woman is a different explanation of its purpose.[17] It has been suggested that they were used for education of young girls to teach about the stages of menstruation as well as the female body. Many other theories suggest alternative functions for these sculptures. One element to always consider is these ideas are speculation, as we have no concrete evidence to suggest the function of this object during it’s time.

Through analyzing some of the facts surrounding The Venus of Dolni Vestonice, the function of the object becomes unclear. It is stated in the book, Women in Human Evolution, that through grouping the “Venus” figurines together across large geographical areas and exploiting the figurines that have the more voluptuous features, the meaning becomes skewed by the evidence acquired in other cultures and areas.[18] Stereotyping of these similar sculptures begins to slant the evidence and the meanings, when the evidence does not support the ideas.

The Venus of Dolni Vestonice is a small ceramic sculpture created during the Upper Paleolithic Age. It was discovered in a burial site near the modern day Czechoslovakia. It has a known fingerprint of a child. Little is known of the religious, fertility, or burial practices of the culture that created this object. What remains known is the location, surrounding objects, site of excavation, and the object itself. The other ideas surrounding this figurine are merely ideas developed through interpretations of the object and its purpose.

The Venus of Dolni Vestonice is the subject of my research for many reasons. The object itself is very beautiful and interesting and the fact that it is a female figure is also appealing. Theories relating the figure to reproduction and fertility relate the object’s content to my own work. One aspect of the artifact that also catches my attention is that it is the oldest known ceramic object, which is also a sculpture, not a vessel. The most fascinating aspect of this object, like many from the past are the unknowns, in which are filled and skewed with contemporary concepts and ideals, that in turn, hinder our ability to completely understand any object from the past.

[1] “Venus of Dolni Vestonice, Czech Prehistoric Ceramic Figurine: Characteristics, Photograph”. http://www.visual-arts-cork.com/prehistoric/venus-of-dolni-vestonice.htm

[2] “Dolni Vestonice(Czech Republic).” http://archaeology.about.com/od/dterms/g/dolnivestonice.htm

[3] “Venus of Dolni Vestonice “ as in note 1.

[4] “Venus of Dolni Vestonice “ as in note 1.

[5] “Venus of Dolni Vestonice “ as in note 1.

[6] “Venus of Dolni Vestonice “ as in note 1.

[7] Chris Gosden, as in note 6, 98.

[8] Upper Paleolithic, Dictionary.com, http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/Upper+Palaeolithic

[9] As in n Note 2.

[10] As in n Note 2.

[11] As in n Note 2.

[12] William R. Uttal. Dualism: The Original Sin of Cognitivism. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ. 2004, 57.

[13] Chris Gosden, as in note 6, 98.

[14] As in n Note 2.

[15] Chris Gosden, Prehistory: A Very Short Introduction, Oxford University Press. Oxford, England. Publication Year: 2003, 97.

[16] Jean M. Coyle, ed. Handbook on Women and Aging. Greenwood Press: Westport, CT 1997, 42.

[17] Chris Gosden, as in note 6.

[18] Lori D. Huger – editor. Women in Human Evolution. Routledge. London: 1997, 99.

Angela Waite

Myceneaen Pottery is so beautiful and striking because of the combination and coordination of form and content. The forms are usually very simple rounded vessels that swell in one area. This pot swells at the bottom and constricts at the top. At the point where the pot starts its neck and spout, a band decorates the pot, separating the two parts. The top part; neck spout and handle farther separates itself from the main body of the pot with color differentiation. Myceneaeans decorated their pottery with beautiful abstract rounded and flowing line drawings. The drawings also emphasis the form of the pot; this pot has more lines in the heaviest areas of the pot. The drawing of the bird also relates to the bird like shape of the pot, with its round bottom that moves up into a neck and then into a spout or beak.

Stasya Berber

Early ceramics: Cuneiform

Cuneiform tablets and tokens were first observed in the artifacts of the Sumer people in early Mesopotamia in the 30th century B.C. some 3000 years ago. The Sumer developed a unique pictorial script using a reed stylus to carve wedge shaped marked into wet clay. The clay was allowed to dry out in the sun, or if used for official means it was baked. Often, these baked tablets were also covered with clay envelopes and sealed with wax for privacy until the recipients could open them.

Babylonians, Akkadians and Assyrians whom lived in closed proximity to the Sumer people also utilized cuneiform glyph writing according to their differing dialects. Our Indo-European language emerged from the early Syrian and Iranian peoples of present day Turkey whom also used cuneiform to represent sounds.

Thus, Clay cuneiform tablets, though small enough to be held in the hand, are historically invaluable as they record the development of proto alphabets in early Persia, and record the daily and official lives of the people of Mesopotamia. Brown University – which houses over 20 of these clay tablets has translated some 200 specific cuneiform symbols which may have been memorized by specialized members of the society. The tablets were used for government documentation, to record sales and taxes (Nicholas Kammer. Brown University 2002).

Bambi Freeman

Sarcophagus of the Spouses